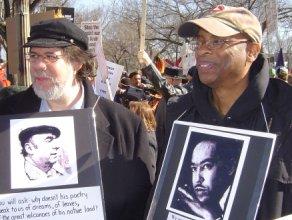

Martin Espada and E. Ethelbert Miller, photo courtesy of Reginald Dwayne Betts.

Martin Espada is a poet and English professor at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. His eighth collection of poems, The Republic of Poetry, was published last October. He is, in the words of writer Sandra Cisneros, “the Pablo Neruda of North American authors.” He talks here with poet E. Ethelbert Miller. You can read his poem “Jorge the Church Janitor Finally Quits” here .

E. Ethelbert Miller: Do you walk around with a rainforest in your head?

Martin Espada: Yes, I do. The rainforest in question is called El Yunque (The Anvil) in Puerto Rico. I’ve been there many times in reality, and many more times in my head. The moist green light at El Yunque is still the essence of the island for me. This means history, origins, family. My father was born in the mountains of Puerto Rico; my cousin actually works at El Yunque.

The reference comes from an early poem of mine, “Puerto Rican Autopsy:” “Winter-corpsed/ in East Harlem,/ opened his head/ and found/ a rain forest.” That poem was written more than 25 years ago. At the time, the only place I knew outside the United States was Puerto Rico. Since then, I have seen much more of the world, and so there are other places in my head, occupying space with that rainforest. There is a plaza in the town of Tepoztlan, Mexico, where I witnessed a Zapatista rally before they marched on Mexico City. There is a shantytown in Managua, Nicaragua where I helped to dig latrines three years after the Sandinista revolution. There is Neruda’s house at Isla Negra in Chile, where I participated in the celebration of his centenary in 2004, reading Whitman aloud in Spanish at the poet’s tomb on a cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean. My perspective is now much more pan-Latin that it was in my youth.

E. Ethelbert Miller: We both came out of public housing in New York City. Do you find this experience still singing a song in your imagination?

Martin Espada: I spent my entire childhood in public housing, growing up in the East New York section of Brooklyn. This had to shape my imagination. I recently returned there after many years in the company of Mari McQueen, a childhood friend who is now a writer and editor at Consumer Reports. Mari put those years in perspective. She said: “Everyone who comes out of this place has a hard edge… We learned early in life that disrespect has serious consequences, up to and including death.” Mari remembered what I had forgotten.

I ended up writing a poem about this experience of going back, called “Return,” which recalls a fight in the street in front of my building 40 years ago, a thrown can clanging off my head, blood everywhere, me banging on doors in the hallway for help. That’s a song, I suppose, but it’s a song of grief on the one hand, and a song to survival on the other.

E. Ethelbert Miller: Does a Puerto Rican writer today still write out of a feeling of dislocation?

Martin Espada: A Puerto Rican writer from New York is doubly dislocated: first, there is dislocation from Puerto Rico; secondly, there is Puerto Rico’s dislocation from itself. Puerto Rico is a colony of the United States. It may be a truism that you can’t go home again, but it’s especially true when home is an occupied territory. A Puerto Rican writer from New York, like myself, is twice alienated. I never forget that in this country I belong to a marginalized, silenced, even despised community; yet, in Puerto Rico, as a “Nuyorican” poet, I am marginalized again, for reasons related and unrelated to the island’s colonial status.

Strangely enough, this sense of never being at home, this sense of not truly belonging anywhere, produces a friction that sets off the sparks of poetry. If I am always at the margins, then I am by necessity the observer; if I am always on the outside, then I am by definition independent; if I am never anchored to one place, then I am free to wander; if I am never blinded by loyalty, then I am free to speak the truth as I see it.

E. Ethelbert Miller: Were there elements of an aesthetic in your father’s photography that you “sampled” for the creation of your poems?

Martin Espada: My father, Frank Espada, was working as a draftsman for an electrical contracting company when I was born in 1957. His great love, however, was photography. As a photographer, he directed the Puerto Rican Diaspora Documentary Project, a photo-documentary and oral history of the Puerto Rican migration. His images hung on the walls of our apartment, and thus the walls of my imagination, from earliest memory.

No doubt this influenced the visual sensibility in my work, the sense of light and shadow. My father’s photography also influenced my subject matter and perspective. I am a political poet, to a large extent, because I grew up in the household of a political activist and artist.

E. Ethelbert Miller: When did you discover the poetry of Pablo Neruda?

Martin Espada: There was no great epiphany in my discovery of Neruda (or, for that matter, in the discovery of another major influence, Walt Whitman). Neruda came to me gradually.

I recall finding his poems in a collection edited by Robert Bly while rummaging through a used bookstore in Madison, Wisconsin, where I did my undergraduate work in the late 1970s. I slowly realized the vastness of Neruda, and soon I began to swim in that ocean. I now teach a course on the life and work of Neruda at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

E. Ethelbert Miller: You mentioned in a interview (Bloomsbury Review, Sept.-Oct. 2006) that there are many Nerudas. Which one is the most important to you? Why?

Martin Espada: There are, indeed, many Nerudas: the love poet, the surrealist poet, the poet of the sea, the poet of everyday things, the political poet, the poet of the historical epic. Certainly, the last two Nerudas matter most to me. There are several reasons. Neruda demonstrates the ways in which we can channel anger into art. In his first book of political poetry Spain in the Heart, about the Spanish Civil War, there are poems of artful anger like “I Explain a Few Things” and “General Franco in Hell,” works of intense fury that are also grounded in the image, in particulars. Neruda also articulates the role of the poet as advocate, speaking on behalf of others who will never have the opportunity to speak for themselves. We see this in Canto XII of “Heights of Macchu Picchu,” where he addresses centuries of dead laborers and says: “I come to speak for your dead mouths.”

Without the example set by Neruda in Canto General, his epic history of Latin America in verse, I never would have written historical poems about Puerto Rico such as “Rebellion is the Circle of a Lover’s Hands,” about the Ponce Massacre in 1937, or “Hands Without Irons Become Dragonflies,” an elegy for the poet Clemente Soto Velez, my friend and mentor, which is also a history of the independence movement in Puerto Rico against both Spain and the United States. This Neruda enables me to see myself as part of a great tradition, which goes back to Whitman and encompasses other influences of mine, from Langston Hughes to Allen Ginsberg.