The past colonial possessions of the United States seem to have slipped from public consciousness. Most American troops left Cuba, the Philippines, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic many decades ago, so little more could be expected of a nation that hardly remembers the two wars it is currently fighting.

The past colonial possessions of the United States seem to have slipped from public consciousness. Most American troops left Cuba, the Philippines, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic many decades ago, so little more could be expected of a nation that hardly remembers the two wars it is currently fighting.

But the blank stares that follow the mention of Guam or the Mariana Islands should not be dismissed as easily. The Mariana Islands, an archipelago in the south Pacific, are politically divided between the Territory of Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Guam, the largest island, has been a U.S. territory since 1898, except for the few years during World War II when it was under a brutal Japanese occupation. The United States seized the other islands from the Japanese near the end of the war and continued to control them after the war as part of the UN trust administration.

The legal status of the islands can sound complicated, but practically it’s very simple. As unincorporated territories of the United States, they cannot become states. They lack voting representatives in Congress, and remain on the UN list of non-self-governing territories. In other words, they are modern-day American colonies, a legacy of a past that isn’t fully past.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the question of whether this was legal went all the way to the Supreme Court. In a number of cases decided in 1901, the Court declared that unincorporated territories belong to the United States but are not part of it, and therefore residents of such territories lack constitutional rights even if they are citizens. As the old joke goes, the Constitution follow the flag, but it never catches up.

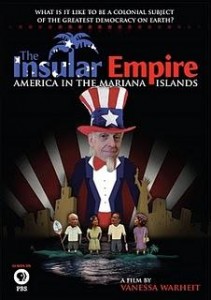

The Insular Empire, a documentary by filmmaker Vanessa Warheit, tells the story of the Chamorro people, the indigenous inhabitants of those islands. Over centuries, foreigners shaped the Chamorro existence, first the Spanish colonizers, and then the Japanese and Americans. Through the life stories of four Chamorro-Americans who have struggled to protect their cultural and political rights, the film shows both the good and bad that American trusteeship has wrought in the far-flung territories.

Strikingly, the Chamorro inhabitants lack animosity toward their adopted country. In fact, patriotism is as present there as in any part of the United States, and people from the Mariana Islands serve in the army and die for their country at higher per-capita rates than any state. They speak English, share the same dreams of any American, and hardly complain that a third of their land is off limits to them by military bases.

Yet this effectively colonial relationship contravenes all principle of self-determination and democracy, core American values. Worse, the Department of Defense is currently planning a military buildup in Guam that would drastically expand bases, damage the land, and further restrict areas that inhabitants have access to. Without any real representation, the Chamorro are powerless to stop it.

As one Chamorro says in the film, “People here are not aware of this relationship, and if they are not aware, what is the solution?” The same could be said about Americans in the 50 states, who are largely unaware of what is happening. Indeed, Washington can do what it likes in the Marianas because few voters know or care about what is happening. By raising uncomfortable questions about the vestiges of imperialism in our democracy, The Insular Empire is effective at telling the story of a people whose perspective has been absent for far too long.