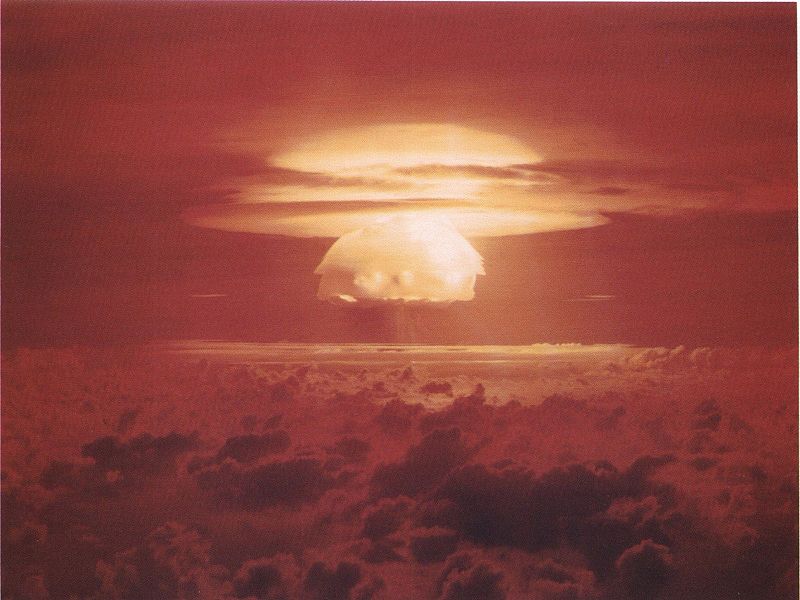

The 56th anniversary of the first U.S. hydrogen bomb test was on March 1. Code-named Bravo, the test took place at Bikini Atoll, a ring of tiny coral islands in the central Pacific.

The 56th anniversary of the first U.S. hydrogen bomb test was on March 1. Code-named Bravo, the test took place at Bikini Atoll, a ring of tiny coral islands in the central Pacific.

Commemorations in affected communities in Japan, Hawai’i, and Pacific Island nations featured testimonies from those living with the long-term effects of radiation sickness, many forms of cancer, and extreme social and cultural dislocation caused by nuclear experimentation. Alongside these testimonies on Nuclear Survivors Remembrance Day were continued calls for just compensation for loss of life, land, and livelihood, as well as for eradication of nuclear weapons worldwide.

The experience of the Marshall Islanders serves as a chilling reminder of the deadly legacy of nuclear weapons that has already affected survivors for nearly 60 years. Recognizing the ongoing severe dangers of nuclear proliferation, in April 2009 President Obama announced that the administration will work for strategic nuclear arms reduction between the United States and Russia, to strengthen the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), and toward a comprehensive test ban treaty. But Obama should also help the Marshall Islanders more directly.

A Thousand Hiroshimas

The triumphantly named Bravo detonation was a thousand times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima at the end of World War II. According to the New Zealand-based Nuclear Age Peace Foundation, the explosion “gouged out a crater more than 200 feet deep and a mile across, melting huge quantities of coral, which were sucked up into the atmosphere together with vast volumes of seawater.” Particles of radioactive fallout landed on the downwind island of Rongelap (125 miles away) to a depth of one-and-a-half inches in some places, and radioactive mist appeared on Utirik (300 miles away). The U.S. navy did not send ships to evacuate the people of Rongelap and Utirik until three days after the explosion.

The U.S. government chose Bikini because the location was far from major air or shipping lanes, In February 1946 Commodore Ben H. Wyatt, then the U.S. military governor of the Marshall Islands, traveled to Bikini to ask the people if they would leave their atoll temporarily so that the United States could test atomic bombs for “the good of mankind and to end all world wars.” The islanders agreed to this lofty-sounding goal. Fifty-six years later, they still cannot return to their island due to the continuing effects of radioactive contamination on the land, water, vegetation, fish, and shellfish. Bikini Atoll remains uninhabitable to this day.

Indeed, the radioactive legacy of 67 nuclear tests conducted by the United States in the Marshall Islands between June 1946 and August 1958 continues to wreak havoc on the health of Marshallese people and others in Micronesia affected by the fallout. In the years following the explosions many women miscarried. Others gave birth to stillborn babies or to “jellyfish” babies without heads, limbs or skeletons. Since then, survivors and their descendants have developed many forms of cancer. They have been shuttled from one overcrowded, makeshift home to another, without adequate support or livelihood. Some 3,000 Marshallese live in Hawai’i, where they seek medical treatment for cancer and other health issues associated with nuclear testing and displacement from their homeland.

Survivors are active in ERUB (the acronym for Enewetak, Rongelap, Utirik and Bikini Atolls, islands impacted by the U.S. nuclear testing program). In the Marshallese language, erub means broken or shattered. Organizers say that it “symbolizes the breaking up of our once close-knit communities which were displaced due to the nuclear testing program.”

Obama’s Nuclear Policy

In a recent speech at the National Defense University, Vice President Joe Biden renewed the Obama administration’s stated commitment to the reduction and eventual elimination of nuclear weapons, noting that, in the meantime, the administration has increased funding to maintain the U.S. nuclear stockpile and modernize its nuclear infrastructure.

Biden acknowledged: “As both the only nation to have used nuclear weapons, and as a strong proponent of nonproliferation, the United States has long embodied a stark but inevitable contradiction.” He noted that the United States has “long relied on nuclear weapons to deter potential adversaries,” but argued that “as our technology improves, we are developing non-nuclear ways to accomplish that same objective” including an adaptive missile defense shield and conventional warheads with worldwide reach.

The administration’s approach is to support a series of agreements for strategic nuclear arms reduction between the United States and Russia, a comprehensive test ban treaty, and a non-proliferation treaty. These are important developments, but Barry Blechman, co-editor of Elements of a Nuclear Disarmament Treaty, calls such steps “piecemeal agreements,” and urges a much more comprehensive approach. “Those possessing the largest arsenals — the United States and Russia — would make deep cuts first.” Nations with smaller arsenals “would join at specified dates and levels.” He claims that “international precedents already exist for virtually every procedure necessary to eliminate nuclear weapons safely, verifiably and without risk to any nation’s security.'”

The NPT Review Conference in New York this May will be a crucial test of the international community’s will and ability to unite toward this goal. Obama will be there, together with government officials and members of nongovernmental organizations from many nations. Among the crowds, atomic-bomb survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki will attest to their own ghastly experience of nuclear weapons, together with people from the Marshall Islands, including former senator of the Marshall Islands Abacca Anjain-Maddison. She argues that the islanders’ experiences of the terrible long-term damage from Cold War nuclear experiments give them a unique and authoritative voice in this discussion.

Obama should use all the power of his office to support Anjain-Maddison’s call for a world free of nuclear arms. He should rally nuclear and non-nuclear governments to strengthen the NPT, make major cuts in the U.S. nuclear arsenal, and pressure other nuclear powers to make cuts in their stockpiles. He should hold out the vision that a world free of nuclear weapons is possible and commit the United States to making this a reality.

In addition, he should support the Republic of the Marshall Islands Changed Circumstances Petition submitted to Congress, seeking adequate compensation beyond what has already been paid, for personal injuries, property damages, medical care programs, and radiological monitoring related to the nuclear testing program conducted in the Marshall Islands.

When it comes time to commemorate the next Nuclear Survivors Remembrance Day, let’s hope that the United States is much further down the road toward nuclear disarmament than it is today.