Activist artist Ellen O’Grady visits Hebron, the only Palestinian city outside East Jerusalem where Israeli settlers occupy the city center.

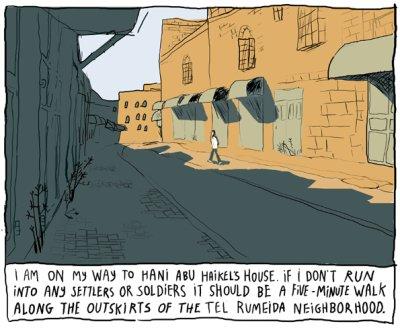

I am on my way to Hani Abu Haikel’s house. If I don’t run into any settlers or soldiers it should be a five-minute walk along the outskirts of the Tel Rumeida neighborhood.

I am on my way to Hani Abu Haikel’s house. If I don’t run into any settlers or soldiers it should be a five-minute walk along the outskirts of the Tel Rumeida neighborhood.

My journey begins on Shuhadda Street, a once-bustling thruway of stone buildings whose soul left when the restaurant-owners and barbers and shoe-repairmen shut and barred their wide steel doors for good. Since the Israeli Defense Forces declared it off limits to Palestinians for the safety of local settlers, few families remain. Today, my only living company along this boulevard is a few scraggles of grass creeping up through cracks.

Just before I reach the Beit Hadassah settlement, I take a right turn up the outdoor staircase and a quick left off the stairway passing the Cordoba school, then right, again, up a steep path to circle around the heavily-guarded Tel Rumeida settlement. As I was instructed, I check to see if any settlers are at the well or occupying Issa’s house, a concrete building which stands vacant in front of Hani’s. Both appear empty, so I continue, peeking into the house as I walk by. The view through Issa’s glassless window reveals the work of vandals—walls covered with Hebrew graffiti and Israeli flags.

Just before I reach the Beit Hadassah settlement, I take a right turn up the outdoor staircase and a quick left off the stairway passing the Cordoba school, then right, again, up a steep path to circle around the heavily-guarded Tel Rumeida settlement. As I was instructed, I check to see if any settlers are at the well or occupying Issa’s house, a concrete building which stands vacant in front of Hani’s. Both appear empty, so I continue, peeking into the house as I walk by. The view through Issa’s glassless window reveals the work of vandals—walls covered with Hebrew graffiti and Israeli flags.

Olive trees line the terraces leading to Hani’s home at the top of the hill. Hani tells me the trees are hundreds, some maybe even a thousand, years old. They call the olives Roman olives. Their oil is heavy and expensive, “like a diamond.” Hani had good income from the olives until settlers burned and cut down over 200 of his trees—half what he owned.

Over 100 years ago, the Abu Haikel family bought this crest of hill in the Tel Rumeida neighborhood of Hebron. Jameel Abu Haikel built his house on the family property in 1947, the same house where his son Hani now lives with his wife, mother and children. Hani says when he was a child in the 1970s it was a beautiful area, quiet and safe. In the early 1980s, however, after archaeologists claimed that Tel Rumeida might be the site of King David’s first palace, a group of Israeli settlers brought in six portable caravans and mounted them directly over the excavation site, just beside Hani’s home. Ever since, the land around the settlement has slowly been taken over and the Abu Haikels have suffered constant harassment. The settlers throw stones, bottles, and curses. They dump garbage onto the land and house, sever and pour paint on the family’s grape vines, and burn their cars and olive trees. Like many of the Palestinian residents of Tel Rumeida, the Abu Haikels have fortified the windows of their homes with metal bars and they keep a careful watch over their children. Just a few weeks before my visit, Hani’s son Jamil broke his leg when he was running from stone-throwing settler children. Because Palestinians are forbidden to drive vehicles into the neighborhood, Jamil, now unable to walk a far distance, cannot go to school.

Over 100 years ago, the Abu Haikel family bought this crest of hill in the Tel Rumeida neighborhood of Hebron. Jameel Abu Haikel built his house on the family property in 1947, the same house where his son Hani now lives with his wife, mother and children. Hani says when he was a child in the 1970s it was a beautiful area, quiet and safe. In the early 1980s, however, after archaeologists claimed that Tel Rumeida might be the site of King David’s first palace, a group of Israeli settlers brought in six portable caravans and mounted them directly over the excavation site, just beside Hani’s home. Ever since, the land around the settlement has slowly been taken over and the Abu Haikels have suffered constant harassment. The settlers throw stones, bottles, and curses. They dump garbage onto the land and house, sever and pour paint on the family’s grape vines, and burn their cars and olive trees. Like many of the Palestinian residents of Tel Rumeida, the Abu Haikels have fortified the windows of their homes with metal bars and they keep a careful watch over their children. Just a few weeks before my visit, Hani’s son Jamil broke his leg when he was running from stone-throwing settler children. Because Palestinians are forbidden to drive vehicles into the neighborhood, Jamil, now unable to walk a far distance, cannot go to school.

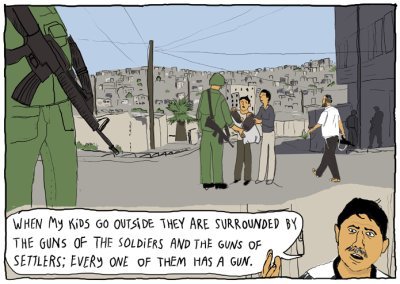

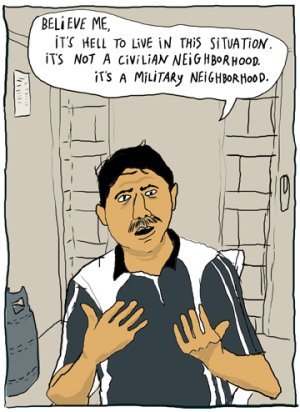

“Believe me, it’s hell to live in this situation.” Hani tells me. “It’s not a civilian neighborhood, it’s a military neighborhood. When my kids go outside they are surrounded by the guns of the soldiers and the guns of settlers—every one of them has a gun. The settlers are harassing us step by step. In the past we had five families living in this building, now there is just our family.”

“Believe me, it’s hell to live in this situation.” Hani tells me. “It’s not a civilian neighborhood, it’s a military neighborhood. When my kids go outside they are surrounded by the guns of the soldiers and the guns of settlers—every one of them has a gun. The settlers are harassing us step by step. In the past we had five families living in this building, now there is just our family.”

Hani fights back by sharing his experiences with Israelis and internationals. He works with a number of Israeli peace organizations, including Breaking the Silence, an organization of veteran Israeli soldiers that collects testimonies of soldiers who served in the Occupied Territories and provides guided tours of Hebron—a place where many of the members were stationed. A week ago Breaking the Silence brought to Hani’s a group of 50 Israeli youth who were soon to enter the army.

“When they go into the army they will be brainwashed and prepared for battle,” Hani says. “They will not be told they will be meeting civilians and innocent people. I want to talk with them because most of them have not had experiences with Palestinians. They only see Palestinians on TV and see them only as fighters. I asked them, ‘have you ever talked with a Palestinian?’ They said no. So how will they know us if they don’t sit with us? I saw in their body language they were scared to come. However, after my children and I talked to them their body language changed. I showed them a video of settler and soldier harassment. I swear when many left they were crying. They said, ‘We did not believe the Israeli democratic government could do something like that.’ They stayed two hours talking, even though we only scheduled a half hour.

“When they go into the army they will be brainwashed and prepared for battle,” Hani says. “They will not be told they will be meeting civilians and innocent people. I want to talk with them because most of them have not had experiences with Palestinians. They only see Palestinians on TV and see them only as fighters. I asked them, ‘have you ever talked with a Palestinian?’ They said no. So how will they know us if they don’t sit with us? I saw in their body language they were scared to come. However, after my children and I talked to them their body language changed. I showed them a video of settler and soldier harassment. I swear when many left they were crying. They said, ‘We did not believe the Israeli democratic government could do something like that.’ They stayed two hours talking, even though we only scheduled a half hour.

“This is how I fight: not with a gun, but with words, through sitting down and talking.”